The Dangers Of Training Corruption

More Is Just More:

Last weekend I flew to Houston to help Coach Ron Wolforth at The Texas Baseball Ranch with a 3 day Elite Pitchers Boot Camp. I am honored to be a member of the staff at a place where instructors and students are free to innovate and experiment to find better ways to learn and to teach throwing. They pay me to help them, but I would do it for free just to experience my favorite part of every camp – Julio’s Mexican Grill (Formerly Rico’s Hacienda)!

The camps begin at 2:00 pm on Fridays. At the end of the first day, Ron and Jill Wolforth take us all out to dinner at the same place every week. Julio’s a little place about 5 miles from the ranch and features the finest Mexican cuisine in town, tall frosted mugs of Dos Equis, a soft serve ice cream machine.

This is where the magic of the ranch happens.

When the food is served, we all join hands and bow our heads to hear Garret Wolforth recite the same prayer he has been rolling out since he was old enough to speak – “God is great, God is good…” Then, over the distant crooning of American Idol wannabees that can sometimes resemble a walrus giving birth to a piece of farm equipment, Ron, Jill, Flint Wallace, Wes Johnson, Jonathan Massey, all the Ranch hands and any other coaches that might be around fill our gullets, enjoy fellowship, and talk baseball.

This past Friday night the topic turned to a problem that Coach Wolforth recently introduced called “Training Corruption”.

Training Corruption:

“A phenomena that can occur when the body , in an effort to acheive a specific short term training goal, chooses an organization that happens to be either inefficient, misapplied, incomplete, over exaggerated and/ or a detrimental compensation and thereby begins to either denigrate the movement pattern itself or greatly impedes it’s normal development.”

-Coach Ron Wolforth-

Athletes and coaches can induce training corruption by ascribing the idea that more is always better. For example, if 30 reps of a drill is good, then 3000 must be way better. If a humerus-to-forearm angle inside of 90 degrees at final connection is good, then having it inside of 70, or even 50 must be even better.

If flexing your back knee while moving forward, and getting deep into your glutes is good, then getting even deeper must be even better.

If performing shoulder internal rotation and forearm pronation immediately after launch is good, then earlier, more pronounced pronation and internal rotation must be even better.

Of course all of theses are false assumptions.

As coaches, instructors, and parents, we need to aware of negative effects that can occur if we find our athletes becoming what I call “overachievers”. These are the guys that while attempting to correct inefficiencies, incessantly repeat exaggerations of desired movement patterns to the point of creating unintended disconnections.

Exaggerating and repeating desired movement patterns, can be a great tool for learning to feel mechanical efficiency, but there comes a point where it can be detrimental to development and performance.

Listen, I love guys that work hard.

And I love guys that lock in on what they’re trying to work on until they get it done.

I also love banana pudding ice cream.

But although I haven’t yet found a limit to that scrumptious delectable, I’m sure there is a point where more is not better. More is just more, and eventually, more is not healthy.

Here is a case study that taught me a hard lesson on the danger of “training corruption” and nearly derailed a young pitcher’s development:

Nick Little is a 17 year old rising senior at a local high school. Plagued by chronic, debilitating medial elbow pain, the right-hander first checked in for his initial evaluation at the ARMory on August 27, 2014.

Nick’s initial physical assessment revealed deficits in scapular dyskinesia, shoulder internal rotation, thoracic extension, bilateral hip internal rotation, hamstring tightness, ankle mobility, deep squat, hurdle step, and rotational core stability.

During his video analysis, we found significant opportunities or cautions in glute activation, lead leg disconnection, forearm flyout, early torso rotation, glove side disconnection, crossing the acromial line, failure to pronate into launch, no rotation around the front hip, and an elbow that crossed the midline of his body resulting in a late bang on the posterior shoulder.

His initial top velocity was 79 mph.

It may appear that Nick had an extraordinary number of inefficiencies to overcome, but it my experience, with the way young kids are taught to throw these days, Nick’s evaluation was similar to a lot of first time ARMory students. With an intelligent and creative, yet systematic approach, physical and biomechanical constraints can be erased in short order.

When Nick’s evaluation was complete, we wrote up an individualized training plan to eliminate each one of his cautions and significant opportunities.

Nick was all in from the start, opting to skip fall high school baseball with hopes of eliminating his arm pain and gaining enough velocity to attract the attention of some college recruiters.

In the beginning, things appeared to be going well.

Within 3 weeks, Nick’s deceleration pattern had improved, his forearm flyout was gone, and he was able to throw pain free. He kept grinding and by late September his velocity had increased to 87 mph. He looked to be well on his way to achieving his dream of throwing 90 mph earning a college baseball scholarship.

But then in early October, Nick started to feel pain on the outside of his elbow (lateral).  The pain began insidiously and gradually worsened over time.

The pain began insidiously and gradually worsened over time.

Some days were better than others and at times we felt like we were making progress, but the nagging ache persisted through the winter and despite our efforts, he even began to have resting pain above and below his lateral elbow. In early January, I sent him to see Dr. Koco Eaton, and I have to tell you, I was worried.

I had seen a similar patient two years earlier that had come to us with chronic lateral elbow pain. This pitcher was a college guy who, as it turned out, had been throwing without a UCL for several years. The lack of stability in the elbow produced a gapping on the inside of his elbow that allowed a compressive collision on the opposite side. Since the UCL had been completely gone for a long time, there was no pain on the inside of his elbow. He had learned to throw in the low 80s without much trouble. However, when he tried to ramp up his velocity, the repetitive forces on the outside were unsustainable, and he had to choose between throwing 80 mph, having Tommy John surgery, or retiring from baseball.

Thankfully, when Nick had his MRI, the UCL came back clean and Dr. Eaton diagnosed him with a radial nerve entrapment. Nick gladly received cortisone injection and took 2 weeks off from throwing. During that time he also started seeing a chiropractor for Active Release and Graston Technique. He also began a round of physical therapy in our clinic and redoubled his efforts to eliminate his mobility/stability issues from his evaluation.

After 2 weeks Nick began throwing again, but unfortunately, his pain returned immediately. His frustration was palpable, but I promised him we would figure it out. It was at this point that I decided to start over.

I got out my anatomy books and traced the radial nerve from the cervical spine all the way down to the forearm. I noted any place I thought it might be vulnerable to becoming tethered.

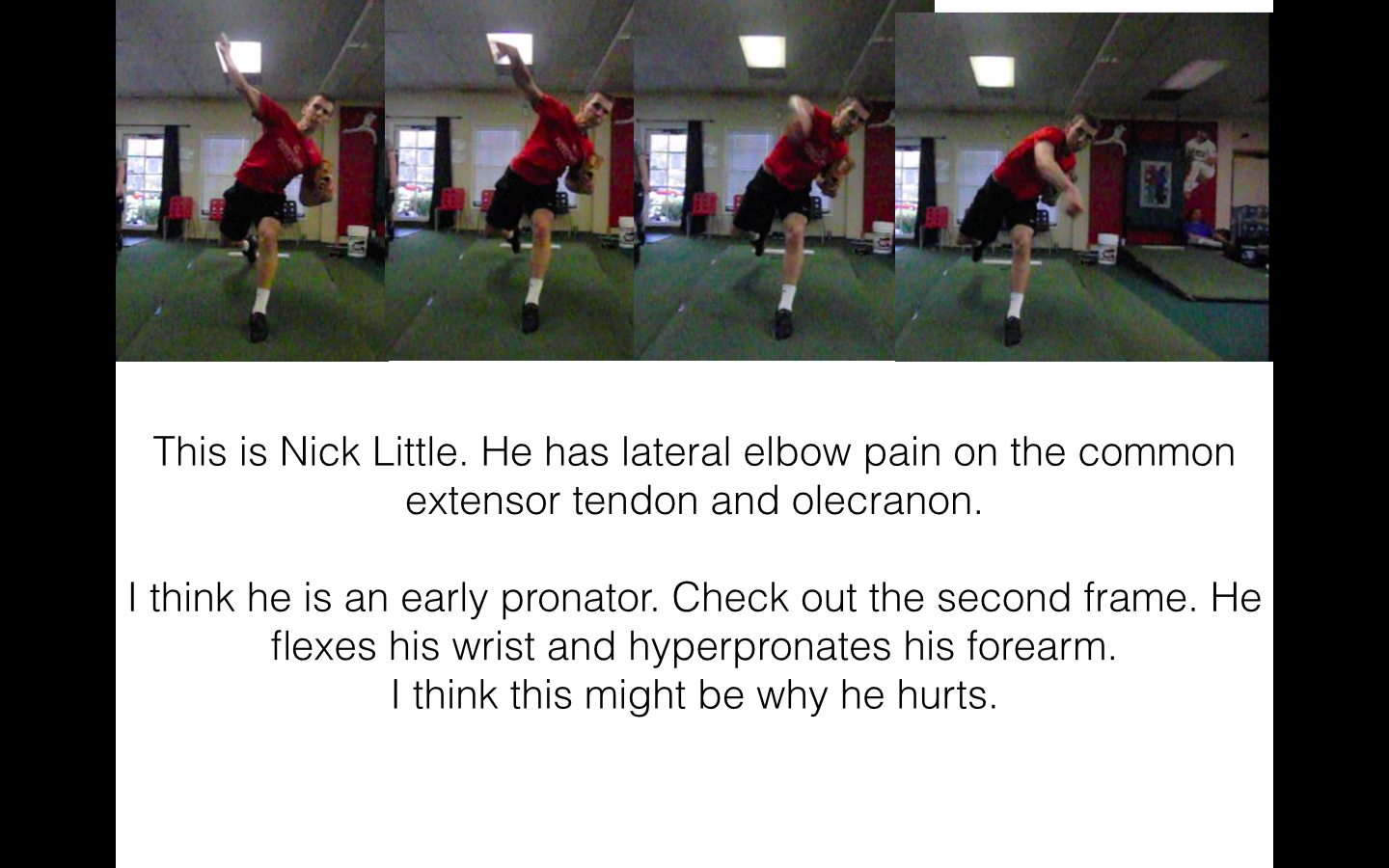

Even though I had looked at dozens of high-speed videos of Nick pitching over the previous 5 month. I shot some more and dug in with a different approach. Instead of looking for movement patterns that we typically judged to be outside the parameters of safety, I scoured Nick’s video for anything in his delivery that was different from most of the guys we see. In our system, we look for and address only gross anomalies in movement. We understand that if the movement pattern is within the parameters of what we know to be safe and healthy, there can be hundreds of individual styles for getting to the end result. Chasing every unique idiosyncrasy in a delivery can lead you down a lot of empty rabbit holes. But since Nick was experiencing debilitating pain, anything atypical might be contributing to his pain. So that’s what I was looking for.

That’s when I found it… the one thing in Nick’s delivery that looked especially different. Just into launch, Nick flexed his wrist and hyperpronated his forearm in an odd way. As I tried to simulate the movement, I realized that the more aggressively I performed it, the more I felt traction on the radial nerve. Sitting at my desk, I repeated it over one hundred times until I began to feel discomfort in my forearm and lateral elbow.

I took some serial photographs of Nick from the front and sent this message to my friend, Wes Johnson at Dallas Baptist University.

Wes agreed and said that he had a guy on his team he thought might have a similar problem.

Now that I had a possible source of the pain the next question was obviously, “What can I do about it?”

Here’s what I did.

Since Nick was being “an overachiever” and pronating prematurely, I thought that even though supination of the forearm at launch is usually something we try to avoid, if I could get him to supinate a little, he might actually end up in a more neutral forearm position. During his next session, I asked Nick if he had ever thrown a cutter. He said he had not, so I grabbed a ball and told him, “throw a cutter.”

With a slightly puzzled look on his face, Nick took a crow hop and threw the first cutter of his life. It was not a good cutter, in fact, it didn’t move at all. It was straight as a board.

But it didn’t hurt.

For the first time in 5 months, Nick had thrown a baseball without pain.

Everyone in the room let out a yelp!

And he did it again.

After a few pain free throws, ARMory Strong director Matt Abramson asked a brilliant question, “If weighted balls help you pronate during deceleration, wouldn’t an underload ball make him pronate less?”

“I guess it would,” I replied.

So Nick took a crow hop and threw an underload ball and reported no pain.

For the next 3 weeks, Nick totally discarded all previous training and threw nothing but cutters, and underload balls… without pain. Eventually, he was able to throw all of his pitches without pain, and now he is back on the mound, playing in travel ball tournaments and topping out at 85 mph and rising. More importantly, he is pain free and the pursuit of his dream of playing college baseball is back on track.

If I am truly honest with myself, I must admit that I caused (or at least contributed to) Nick’s 5 month ordeal with radial nerve irritation. While working to solve his medial elbow pain, I failed to notice him becoming a deceleration “overachiever”. I allowed the corruption of his training to create an unforseen problem.

I will be forever grateful to Nick Little for his perseverance and faith in our process. A player of lesser conviction and drive would have probably given up on us long before we were able to help him find a solution to his pain. But Nick hung in there and kept working with us to find answers. I have no doubt that Nick will break the 90 mph threshold and will achieve his dreams. I know this because I know he will never stop. He will never give up until he gets there.

I’m thankful for the real world education this case gave me and my staff. Working with Nick has improved our knowledge base and understanding of the dynamics and stresses of high level throwing. The experience will aid us in helping hundreds of future students as we move forward in our quest to eliminate throwing pain forever!

Thank you Nick Little!

Now go get what you deserve!

Leave a Reply